Großes Festspielhaus, Salzburg (Detail).

© Thomas Prochazka

[EN] Immortal Performances:

“Così fan tutte” (Glyndebourne, 1951)

Von Thomas Prochazka

II.

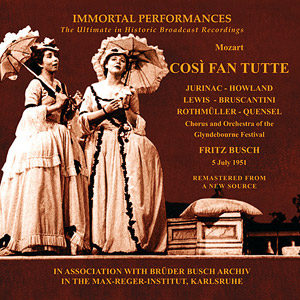

Così fan tutte found a great advocate in the conductor Fritz Busch (1890 – 1951). Busch, who was expelled from Dresden in 1933 by the National Socialists, found a new home in England and a new mission in the Opera Festival founded in 1934 by John Christie on his Glyndebourne estates. Fascinated by Busch’s access to Mozart, the Immortal Performances Recorded Music Society published on Guild in 2005 the performance of July 5, 1951, which was restored on the basis of radio recordings. But Richard Caniell, the leading sound engineer of Immortal Performances, was dissatisfied with the result. What could be more obvious than to take a second try when an acoustically better source became available in the collaboration with the Brothers Busch Archive in Karlsruhe?

The newly revised restoration of this performance has been available since 2009 (IPCD 1004-2). Unfortunately, some sections were irretrievably destroyed. Hence, Caniell was forced to replace these parts from other, acoustically similar performances of Fritz Busch and the singers concerned. — These are the loved and hated challenges of restorers: loved because you can show off your skills and abilities. And hated because it often takes months, sometimes even years, to find suitable substitutes in the interpretation and the acoustic environment, and to connect them with the original material as indiscernible as possible.

In the present restoration, Caniell replaced the sonically unacceptable overture after a few discussions with a recording of similar acoustics from 1940. Furthermore, 2:30 minutes of “Un aura amorosa” from the 1935 Glyndebourne recording (also under Fritz Busch but with Heedle Nash) had to be “borrowed”. Finally, it was necessary to substitute 1:31 minutes of the duet between Fiordiligi and Ferrando from the second act (from the previous year Victor recording of excerpts, also sung by Sena Jurinac and Richard Lewis and also conducted by Busch).

III.

This recording is particularly impressive because of Fritz Busch’s passion for Mozart’s music which just feels “right.” And what an almost somnambulist passion it is. Anyone who only knows Karl Böhm’s studio recording for Decca from 19551 will surely admire the latter’s tempo dramaturgy. However, anyone who has ever heard Fritz Busch’s live recording from Glyndebourne from now on feels the rough edges in the Böhm recording. The over-retarding moments. Sometimes, the latter sounds almost sluggish. Henceforth, curious opera devotees will appreciate Busch’s mastery for the right choice of tempo: for example, in the trios and lively recitatives at the beginning of the evening. (Just listen to the syncopations that add a certain dynamic variety to the recitatives.) Fritz Busch completely convinces the listener in the first act finale: The music bubbles like champagne. And you finally find out who served as model for Rossini’s buffo finali. The string writing in the score in paragraphs [49] and [51] is almost literally quoted in the second act of L’Italiana in Algeri.

Busch’s interpretation never sounds mannered. And seldom pathetic. Even “Per pietà”, Fiordiligis Rondò in the second act, is no exception. And despite the Adagio and the E major key, Mozart’s irony in setting the horn parts tells us: This fortress will also fall.

IV.

The Glyndebourne recording was made at a time when there was no purist insistence to perform every note, when one took the freedom to make cuts: Ferrando’s second aria “Ah, lo veggio, quell’anima bella”, for example, fell victim to the red pencil as well the prelude to the chorus “Bella vita militar” or Dorabella’s aria “È amore un ladroncello”; a recitative part here, a recitative part there. This resulted in a total playing time of approximately 2 hours and 30 minutes. But there are still enough numbers in the score that are marked with “spesso omessa,” “often deleted.” And which may serve as suggestions for the upcoming Salzburg performances to bring down the total playing time to just over two hours without an intermission.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

»Così fan tutte«

Sena Jurinac · Alice Howland · Isa Quensel · Richard Lewis · Marko Rothmüller · Sesto Bruscantini

Chorus and Orchestra of the Glyndebourne Festival

Fritz Busch

Immortal Performances

IPCD

1004-2

Available on

www.immortalperformances.org

V.

With the exception of Sena Jurinac, the 1951 cast may have been considered good but not outstanding. However, those who torture themselves by listening to the last, often heavily advertised Così recordings released by major labels over the past years, will note with sadness that the vocal level was much higher 70 years ago. At that time, mastering legato was a basic requirement for a professional career as a singer.

Isa Quensel, born in Gothenburg, sang the Despina with a soubrette-like tone but not without charm. Fritz Busch had worked with Quensel in 1940 in a Scandinavian production of Così fan tutte. A decade later, he made her shine in Glyndebourne. And not just in “Una donna a quindici anni”. Ingeniously composed, this aria does not pose too great technical demands on the singer (up to the high soprano ‘a’). Opposing Quensel as “game master” was the then 32-year-old Sesto Bruscantini in the role of Don Alfonso. A reliable prompter, enriching every ensemble with his straight tone.

Richard Lewis, born in Manchester in 1914, sang Ferrando. For many years, he demonstrated its versatility singing a repertoire spanning from Monteverdi to Mozart, Gilbert and Sullivan to Britten, Walton and Tippett. Lewis’ lyrical tenor had a bright sound but was never mannered; with low vibrato but good and clear diction. Starting 1947, the Briton became the leading Mozart tenor in Glyndebourne and remained so for the next decade. A quick, but never rushing parlando came off his lips as easily as the lyrical, the feastful moments of his part. This Ferrando performs on a par with Anton Dermota, who is still highly esteemed by Viennese opera devotees (on the Böhm recording from 1955).

Marko Rothmüller sings the Guglielmo with a slim but genuinely sounding baritone. His repertoire included Wagner roles as well as the title role in Alban Bergs Wozzeck. As Guglielmo, his singing never sounds forced. Rothmüller knows how to use legato and portamento correctly. His voice is flexible enough for the parlando passages. In the scenes with Richard Lewis, both voices remain clearly distinguishable.

The first finale offers a special treat with respect to composition and interpretation: When Ferrando and Guglielmo allegedly commit suicide, we hear their syncopated heartbeats in the orchestra — unaccompanied by the voices. In Fritz Busch’s interpretation, we cannot help but notice it. And we ask ourselves how it was possible to miss this musical joke of Mozart until now.

VI.

Alice Howland, an American soprano and the production’s Dorabella, impressed with a clear tone over her entire vocal range. Howland’s diction is easy to understand on the live recording. Her voice shows no “gaps” in or above the passaggio. “Smanie implacabili” is served with verve. Busch let his Dorabella excel with the complete number. He did not cut half the aria like Karl Böhm did to Christa Ludwig.

The 1951 Glyndebourne cast is led by Sena Jurinac as Fiordiligi. Jurinac masters all the difficulties Mozart packed into Fiordiligi’s role2 originally written for Adriana Ferrarese del Bene, the first Fiordiligi and lover of Lorenzo Da Ponte, with astonishing ease. The technical difficulties of “Come scoglio” are well known. Less known is the fact that Fiordiligi’s rondò aria “Per pietà” is full of similar challenges. Here too, Mozart sends the singer’s voice to rise or fall over one and a half octaves. Elisabeth Grümmer’s diction may be clearer, Lisa della Casa’s sound “silvery”: neither of the other two greats achieves Jurinac’s naturalness in vocalization.

VII.

Karl Böhm may have had the better orchestra and the better singers available for his recording. The instinctiveness in Fritz Busch’s interpretation with the Chorus and Orchestra of the Glyndebourne Festival, the audible fun of the ensemble (especially in the Buffo moments) remain unmatched.

Highly recommended.

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Così fan tutte. With Lisa della Casa, Christa Ludwig, Emmy Loose, Anton Dermota, Erich Kunz, Paul Schöffler, Wiener Staatsopernchor, Wiener Philharmoniker, Conductor: Karl Böhm. Redoutensaal of the Hofburg in Vienna, 1955. Decca 455 476-2 (2 CD) ↵

- Please refer to the article “Opera — critical times for an art form? (V)” (in German only) for a detailed discussion of the beginning of “Come scoglio”. ↵